This Is How Your Fear and Outrage Are Being Sold for Profit

The enemy is out there — just check your feed.

One evening in late

October 2014, a doctor checked his own pulse and stepped onto a subway car in

New York City. He had just returned home from a brief stint volunteering

overseas, and was heading to Brooklyn to meet some friends at a bowling alley.

He was looking forward to this break — earlier that day he had gone for a run

around the city, grabbed coffee on the High Line, and eaten at a local meatball

shop. When he woke up the next day exhausted with a slight fever, he called his

employer.

Within 24 hours, he would

become the most feared man in New York. His exact path through the city would

be scrutinized by hundreds of people, the establishments he visited would be

shuttered, and his friends and fiancée would be put into quarantine.

Dr. Craig Spencer had

contracted Ebola while he was treating patients in Guinea with Doctors Without

Borders. He was not contagious until long after he was put into quarantine. He

followed protocol to the letter in reporting his symptoms and posed no threat

to anyone around him while he was in public. He was a model patient — a fact

readily shared by experts.

This did not stop a media

explosion declaring an imminent apocalypse. A frenzy of clickbait and

terrifying narratives emerged as every major news entity raced to capitalize on

the collective Ebola panic.

Social Media exploded

around the topic, reaching 6,000 tweets per second, leaving the CDC and public

health officials scrambling to curtail the misinformation spreading in all

directions. The fear traveled as widely as the stories reporting it. The

emotional response — and the media attached to it — generated billions of impressions

for the companies reporting on it.

Those billions were

parlayed directly into advertising revenue. Before the hysteria had ended,

millions of dollars worth of advertising real-estate attached to Ebola-related

media had been bought and sold algorithmically to companies.

The terror was far more

contagious than the virus itself, and had the perfect network through which to

propagate — a digital ecosystem built to spread emotional fear far and wide.

I’m going to

tell you a few things you probably already know

Every time you open your

phone or your computer, your brain is walking onto a battleground. The

aggressors are the architects of your digital world, and their weapons are the

apps, news feeds, and notifications in your field of view every time you look at

a screen.

They are all attempting to

capture your most scarce resource — your attention — and take it hostage for

money. Your captive attention is worth billions to them in advertising and

subscription revenue.

To do this, they need to

map the defensive lines of your brain — your willpower and desire to

concentrate on other tasks — and figure out how to get through them.

You will lose

this battle. You have already. The average person loses it dozens of times per

day.

This might sound familiar:

In an idle moment you open your phone to check the time. 19 minutes later you

regain consciousness in a completely random corner of your digital world: a

stranger’s photo stream, a surprising news article, a funny YouTube clip. You

didn’t mean to do that. What just happened?

This is not your fault —

it is by design.

The digital rabbit hole

you just tumbled down is funded by advertising, aimed at you. Almost every

“free” app or service you use depends on this surreptitious process of

unconsciously turning your eyeballs into dollars, and they have built

sophisticated methods of reliably doing it. You don’t pay money for using these

platforms, but make no mistake, you are paying for them — with your time, your

attention, and your perspective.

This is not a small,

technical shift in the types of information you consume, the ads you see, or

the apps you download.

This has actually changed

how you see the world.

The War for

Your Attention

Before I go any further,

let me assure you that this is not a list of grievances about the evils of

technology. I am not a Luddite. Like much of humanity, I deeply value my

devices as a helpful prosthesis for my memory, my productivity, and my ability

to connect to the people I care about.

This is instead a sober

evaluation of how the strategies of digitally capturing our attention have

altered us — our lives, our media, and our worldview. These incremental shifts

have added up to enormous changes in our politics, our global outlook, and our

ability to see each other as fellow humans.

Many of the biggest

problems we face in this moment as a society result from decisions being made

by the hidden creators of our digital world — the designers, developers, and

editors that create and curate the media we consume.

These

decisions are not made with malice. They

are made behind analytics dashboards, split-testing panels, and walls of code

that have turned you into a predictable asset — a user that can be mined for

attention.

They do this by focusing

on one over-simplified metric, one that supports advertising as its primary

source of revenue. This metric is called engagement, and emphasizing it —

above all else — has subtly and steadily changed the way we look at the news,

our politics, and each other.

This article is one of a

series exploring how these strategies of capturing our attention are

influencing our lives.

What follows is an

exploration of how the primary artery of our factual information — the News —

has been fundamentally altered by these methods.

How? Let’s look to the

recent past.

The History of

the New

“The Media” as we know it

is not that old. For most of our history the News was, literally, the plural of

the ‘New’ thing(s) people heard about and shared, and was limited by physical

proximity and word-of-mouth. Since the invention of the printing press, the

news consisted of notes posted in public places and pamphlets distributed to

the small number of people who could actually read them.

Between the 18th and 19th

centuries newspapers became fairly common, but were largely opinion rags

containing political essays, sensationalized stories, and eventually

muckraking. They were megaphones for people to exert political influence, and

many had an extremely loose relationship with facts.

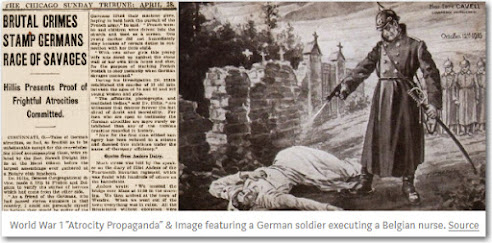

During the lead up to

World War I, unchecked

propaganda from all sides in the news reached a fever-pitch, with

every belligerent participating in a massive fight for public opinion. By the

end of the war it was clear that information warfare was a powerful weapon — it

could raise armies, incite violent mobs, and destabilize whole nations.

In response to this

systematic manipulation of the truth, there was a concerted effort to create an

institution of fact-driven journalism beginning in the 1920's. This process was

ushered forward by the advent of the first mass-media communication networks:

national newspapers and national radio. These slowly gave way to television,

and between these three new platforms, a global media system took hold — buoyed

by the tenets of journalism.

The news continued to have

competitors in the battle for attention, and because of this it continued to

flirt with hyperbole. The drive to sell (papers, ads, products) is naturally

somewhat at odds with the idea of editorial accuracy and measured factual reporting.

Journalistic standards, libel laws, and industry-shaming became common

mechanisms to help curb this slide into sensationalism.

Yet something happened

recently when the news met the internet and began migrating into our pockets:

it started losing the battle for our attention.

The Rise of

Algorithmic Engagement

Here is the rest of the

article very well worth to read it!

https://medium.com/@tobiasrose/the-enemy-in-our-feeds-e86511488de

No comments:

Post a Comment